Lock Free Multithreading With Atomic Operations

文章目录

清空Reeder发现internal/pointers一系列关于多线程的文章,感觉很不错,转载在此。

这是系列第三篇,期待作者继续更新~

Synchronizing threads at a lower level.

The Greek word “atom” (ἄτομος; atomos) means uncuttable. A task performed by a computer is said to be atomic when it is not divisible anymore: it can’t be broken into smaller steps.

Atomicity is an important property of multithreaded operations: since they are indivisible, there is no way for a thread to slip through an atomic operation concurrently performed by another one. For example, when a thread atomically writes on shared data no other thread can read the modification half-complete. Conversely, when a thread atomically reads from shared data, it sees the value as it appeared at a single moment in time. In other words, there is no risk of data races.

In the previous chapter I have introduced the so-called synchronization primitives, the most common tools for thread synchronization. They are used, among other things, to provide atomicity to operations that deal with data shared across multiple threads. How? They simply allow a single thread to do its concurrent job, while others are blocked by the operating system until the first one has finished. The rationale is that a blocked thread does no harm to others. Given their ability to freeze threads, such synchronization primitives are also known as blocking mechanisms.

Any blocking mechanism seen in the previous chapter will work great for the vast majority of your applications. They are fast and reliable if used correctly. However, they introduce some drawbacks that you might want to take into account:

- they block other threads — a dormant thread simply waits for the wakeup signal, doing nothing: it could be wasting precious time;

- they could hang your application — if a thread holding a lock to a synchronization primitive crashes for whatever reason, the lock itself will be never released and the waiting threads will get stuck forever;

- you have little control over which thread will sleep — it’s usually up to the operating system to choose which thread to block. This could lead to an unfortunate event known as priority inversion: a thread that is performing a very important task gets blocked by another one with a lower priority.

Most of the time you don’t care about these issues as they won’t affect the correctness of your programs. On the other hand, sometimes having threads always up and running is desirable, especially if you want to take advantage of multi-processor/multi-core hardware. Or maybe you can’t afford a system that could get stuck on a dead thread. Or again, the priority inversion problem looks too dangerous to ignore.

Lock-free programming to the rescue

The good news: there is another way to control concurrent tasks in your multithreaded app, in order to prevent points 1), 2) and 3) seen above. Known as lock-free programming or lockless programming, it’s a technique to safely share changing data between multiple threads without the cost of locking and unlocking them.

The bad news: this is low-level stuff. Way lower than using the traditional synchronization primitives like mutexes and semaphores: this time we will get closer to the metal. Despite this, I find lock-free programming a good mental challenge and a great opportunity to better understand how a computer actually works.

Lock-free programming relies upon atomic instructions, operations performed directly by the CPU that occur atomically. Being the foundation of lock-free programming, in the rest of this article I will introduce atomic instructions first, then I will show you how to leverage them for concurrency control. Let’s get started!

What are atomic instructions?

Think of any action performed by a computer, say for example displaying a picture on your screen. Such operation is made of many smaller ones: read the file into memory, de-compress the image, light up pixels on the screen and so on. If you recursively zoom into one of those sub-tasks, that is if you break it down into smaller and smaller pieces, you will eventually reach a dead end. The smallest, visible to a human operation performed by a processor is called machine instruction, a command executed by the hardware directly.

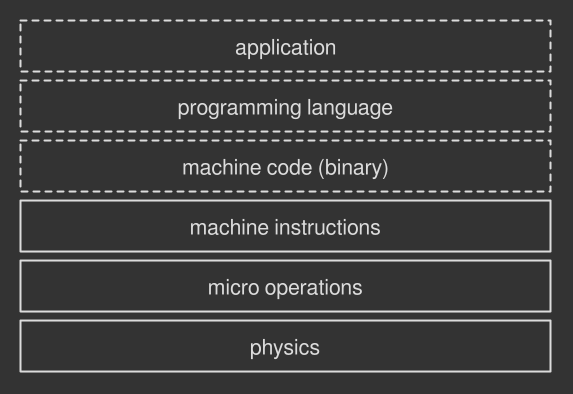

Depending on the CPU architecture, some machine instructions are atomic, that is they are performed in a single, uncuttable and uninterruptible step. Some others are not atomic instead: the processor does more work under the hood in form of even smaller operations, known as micro-operations. Let’s focus on the former category: an atomic instruction is a CPU operation that cannot be further broken down. More specifically, atomic instructions can be grouped into two major classes: store and load and read-modify-write (RMW).

Store and load atomic instructions

The building blocks any processor operates on: they are used to write (store) and read (load) data in memory. Many CPU architectures guarantee that these operations are atomic by nature, under some circumstances. For example, processors that implement the x86 architecture feature the MOV instruction, which reads bytes from memory and gives them to the CPU. This operation is guaranteed to be atomic if performed on aligned data, that is information stored in memory in a way that makes it easy for the CPU to read it in a single shot.

Read-modify-write (RMW) atomic instructions

Some more complex operations can’t be performed with simple stores and loads alone. For example, incrementing a value in memory would require a mixture of at least three atomic load and store instructions, making the outcome non-atomic as a whole. Read-modify-write instructions fill the gap by giving you the ability to compute multiple operations in one atomic step. There are many instructions in this class. Some CPU architectures provide them all, some others only a subset. To name a few:

- test-and-set — writes 1 to a memory location and returns the old value in a single, atomic step;

- fetch-and-add — increments a value in memory and returns the old value in a single, atomic step;

- compare-and-swap (CAS) — compares the content of a memory location with a given value and, if they are equal, modifies the contents of that memory location to a new given value.

All these instructions perform multiple things in memory in a single, atomic step. This is an important property that makes read-modify-write instructions suitable for lock-free multithreading operations. We will see why in few paragraphs.

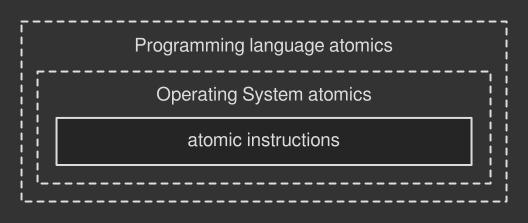

Three levels of atomic instructions

All the instructions seen above belong to the hardware: they require you to talk directly to the CPU. Working this way is obviously difficult and non-portable, as some instructions might have different name across different architectures. Some operations might not even exist across different processor models! So it is unlikely you will touch these things, unless you are working on very low-level code for a specific machine.

Climbing up to the software level, many operating systems provide their own versions of atomic instructions. Let’s call them atomic operations, since we are abstracting away from their physical machine counterpart. For example, in Windows you may find the Interlocked API, a set of functions that handle variables in an atomic manner. MacOS does the same with its OSAtomic.h header. They surely conceal the hardware implementation, but you are still bound to a specific environment.

The best way to perform portable atomic operations is to rely upon the ones provided by the programming language of choice. In Java for example you will find the java.util.concurrent.atomic package; C++ provides the std::atomic header; Haskell has the Data.Atomics package and so on. Generally speaking, it is likely to find support for atomic operations if a programming language deals with multithreading. This way is up to the compiler (if it’s a compiled language) or the virtual machine (if it’s an interpreted language) to find the best instructions for implementing atomic operations, whether from the underlying operating system API or directly from the hardware.

For example, GCC — a C++ compiler — usually transforms C++ atomic operations and objects straight into machine instructions. It also tries to emulate a specific operation that doesn’t map directly to the hardware with other atomic machine instructions if available. The worst-case scenario: on a platform that doesn’t provide atomic operations it may rely upon other blocking strategies, which wouldn’t be lock-free, of course.

Leveraging atomic operations in multithreading

Let’s now see how atomic operations are used. Consider incrementing a simple variable, an task that is not atomic by nature as it is made of three different steps — read the value, increment it, store the new value back. Traditionally, you would regulate the operation with a mutex (pseudocode):

|

|

The first thread that acquires the lock makes progress, while others sit and wait in line until it has finished.

Conversely, the lock-free approach introduces a different pattern: threads are free to run without any impediment, by employing atomic operations. For example:

|

|

I assume that fetch_and_add() and load() are atomic operations based on the corresponding hardware instructions. As you may notice, nothing is locked here. Multiple threads that call those functions concurrently can all make progress. The atomicity of load() makes sure that no reader thread will read the shared value half-complete, as well as no writer thread will damage it with a partial write thanks to fetch_and_add().

Atomic operations in the real world

Now, this example reveals us an important property of atomic operations: they work only with primitive types — booleans, chars, shorts, ints and so on. On the other hand, actual programs require synchronization for more complex structures like arrays, vectors, objects, vectors of arrays, objects containing arrays, … . How can we guarantee atomicity on such convoluted entities with simple operations based on primitive types?

Lock-free programming forces you to think out of the box of the usual synchronization primitives. You don’t protect a shared resource with atomic operations directly, as you would do with a mutex or a semaphore. Rather, you build lock-free algorithms or lock-free data structures, based on atomic operations to determine how multiple threads will access your data.

For example, the fetch-and-add operation seen before can be used to make a rudimentary semaphore that, in turn, you would employ to regulate threads. Not surprisingly all the traditional, blocking synchronization entities are based on atomic operations.

People have written countless lock-free data structures like Folly’s AtomicHashMap, the Boost.Lockfree library, multi-producer/multi-consumer FIFO queues or algorithms like read-copy-update (RCU) and Shadow Paging to name a few. Writing these atomic weapons from scratch is hard, let alone making them work correctly. This is why most of the time you may want to employ existing, battle-tested algorithms and structures instead of rolling your owns.

The compare-and-swap (CAS) loop

Moving closer to real-world applications, the compare-and-swap loop (a.k.a. CAS loop) is probably the most common strategy in lock-free programming, whether you are using existing data structures or are writing algorithms from the ground up. It is based on the corresponding compare-and-swap atomic operation and has a nice property: it supports multiple writers. This is an important feature of a concurrent algorithm especially when used in complex systems.

The CAS loop is interesting also because it introduces a recurring pattern in lock-free code, as well as some theoretical concepts to reason about. Let’s take a closer look.

A CAS loop in action

A CAS function provided by an operating system or a programming language might look like this:

|

|

It takes in input a reference/pointer to some shared data, the expected value it currently takes on and the new value you want to apply. The function replaces the current value with the new one (and returns true) only if the value hasn’t changed, that is if shared_data.value == expected_value.

In a CAS loop the idea is to repeatedly trying to compare and swap until the operation is successful. On each iteration you feed the CAS function with the reference/pointer, the expected value and the desired one. This is necessary in order to cope with any other writer thread that is doing the same thing concurrently: the CAS function fails if another thread has changed the data in the meantime, that is if the shared data no longer matches the expected value. Multiple writers support!

Suppose we want to replicate the fetch-and-add algorithm seen in the previous snippet with a CAS loop. It would look roughly like this (pseudocode):

|

|

In (1) the algorithm loads the existing value of the shared data, then it tries to swap it with the new value until success (2), that is until the CAS function returns true.

The swapping paradigm

As said before, the CAS loop introduces a recurring pattern in many lock-free algorithms:

- create a local copy of the shared data;

- modify the local copy as needed;

- when ready, update the shared data by swapping it with the local copy created before.

Point 3) is the key: the swap is performed atomically through an atomic operation. The dirty job is done locally by the writer thread and then published only when ready. This way another thread can observe the shared data only in two states: either the old one, or the new one. No half-complete or corrupted updates, thanks to the atomic swap.

This is also philosophically different from the locking approach: in a lock-free algorithm threads get in touch only during that tiny atomic swap, running undisturbed and unaware of others for the rest of the time. The point of contact between threads is now shrinked down and limited to the duration of the atomic operation.

A gentle form of locking

The spin until success strategy seen above is employed in many lock-free algorithms and is called spinlock: a simple loop where the thread repeatedly tries to perform something until successful. It’s a form of gentle lock where the thread is up and running — no sleep forced by the operating system, although no progress is made until the loop is over. Regular locks employed in mutexes or semaphores are way more expensive, as the suspend/wakeup cycle requires a lot of work under the hood.

The ABA problem

Instructions in lines (1) and (2) are atomic indeed, yet distinct. Another thread might slip through the cracks and change the value of the shared data once has been read in (1). Specifically, it could turn the initial value, say A, into another value, say B, and then bring it back to A right before the compare and swap operation has started in (2). The thread that is running the CAS loop wouldn’t notice the change and perform the swap successfully. This is known as the ABA problem: sometimes you can easily ignore it if you algorithm is simple as the one above, sometimes you want to prevent it instead as it would introduce subtle bugs in your programs. Luckily there are several workarounds for this.

You can swap anything inside a CAS loop

The CAS loop is often used to swap pointers, a type supported by the compare-and-swap operation. This is useful when you want to modify a complex collection of data like a class or an array: just create the local copy, modify it as needed and then when ready swap a pointer to the local data with a pointer to the global data. This way global data will point to the memory allocated for the local copy and other threads will see up-to-date information.

This technique allows you to successfully synchronize non-primitive entities, yet is difficult to make it work correctly. What if, after the swap, a reader thread is still reading the old pointer? How to properly delete the previous copy without generating dangerous dangling pointers? Once again engineers have found many solutions such as using a language that supports [garbage collection](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garbage_collection_(computer_science) or esoteric techniques like epoch-based memory reclamation, hazard pointers or reference counting.

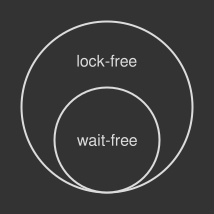

Lock-freedom vs. wait-freedom

Every algorithm or data structure based on atomic operations can be clustered into two groups: lock-free or wait-free. This is an important distinction when you have to evaluate the impact of atomic-based tools on the performance of your program.

Lock-free algorithms allow the remaining threads to continue doing useful work even if one of them is temporarily busy. In other words, at least one thread always makes progress. The CAS loop is a perfect example of lock-free because if a single iteration of the CAS loop fails, it’s usually because some other thread has modified the shared resource successfully. However, a lock-free algorithm might spend an unpredictable amount of time just spinning, especially when there are many threads competing for the same resource: technically speaking, when the contention is high. Pushing it to the limits, a lock-free algorithm could be far less efficient with CPU resources than a mutex that puts blocked threads to sleep.

On the other hand in wait-free algorithms, a subset of lock-free ones, any thread can complete its work in a finite number or steps, regardless of the execution speed or the workload level of others. The first snippet in this article based on the fetch-and-add operation is an example of a wait-free algorithm: no loops, no retries, just undisturbed flow. Also, wait-free algorithms are fault-tolerant: no thread can be prevented from completing an operation by failures of other processes, or by arbitrary variations in their speed. These properties make wait-free algorithms suitable for complex real-time systems where the predictable behavior of concurrent code is a must.

Wait-freedom is a highly desired property of concurrent code, yet very difficult to obtain. All in all, whether you are building a blocking, a lock-free or a wait-free algorithm the golden rule is to always benchmark your code and measure the results. Sometimes a good old mutex can outperform fancier synchronization primitives, especially when the concurrent task complexity is high.

Closing notes

Atomic operations are a necessary part of lock-free programming, even on single-processor machines. Without atomicity, a thread could be interrupted halfway through the transaction, possibly leading to an inconsistent state. In this article I have just scratched the surface: a new world of problems opens up as soon as you add multicores/multiprocessors to the equation. Topics like sequential consistency and memory barriers are critical pieces of the puzzle and can’t be overlooked if you want to get the best out of your lock-free algorithms. I will cover them all in the next episode.